It all began in 1946. Argentina was facing a plummeting economy and massive social unrest, and the country was open to exploring just about any new possibilities – even possibilities such as Juan Perón, who first came into power the same year. It was then that the government made a rather desperate attempt to provide a quick fix for the economy, and the effects, while not as immediately obvious as those of the notorious president, are still becoming ever-more problematic to this day. An unusual shipment flown in from the other end of the world was delivered to the south of Argentina: fifty live Canadian beavers.

At first glance the idea might appear reasonable, or even ingenious. Argentina intended to establish a fur trade; but not by fur-farming, the beavers would instead be released straight into the environment to spread and procreate. Over following years the country would have the permanent and, at the time, much sought-after resource of beaver pelts – one that would provide abundant jobs for trappers and traders. And as much as anything, the gesture served as a much-needed publicity stunt. A short film would appear soon afterwards in cinemas in Buenos Aires: it described what ideal conditions Argentinian forests offered for beavers and what a brilliant future they offered Argentina; and it showed their release, at a scenic location at Lake Fagnano in the centre of Tierra del Fuego. Blurry black and white footage depicted the animal’s rumps as they ambled off into the undergrowth, while a solemn voice declared prophetically, incase the clip had seemed somewhat anticlimactic on its own: “Now they are in God’s hands.”

Castor canadensis – a quite small but not at all shy young beaver, whom I met with on a summer’s day in Tierra del Fuego. (Photo by Jill Schinas)

The divine entity certainly seemed to be more concerned about the welfare of the rodents than that of the nation. Over the following years fur-farming became the very least pressing issue in Argentine politics, and meanwhile the forgotten beavers thrived. Tierra del Fuego might have been specifically created for them; a rich, untouched, beaver-paradise flowing with an almost infinite number of streams, lakes, and channels, draped from head to toe with a lush forest of trees for them to eat and build their dams and lodges with, and most of all, utterly devoid of any of their predators. Fifty years later they numbered in the tens of thousands, and inhabited not just Argentina but neighbouring parts of Chile as well – by which time, the drawbacks of introducing the animals were already all too obvious.

A couple of months which we recently spent cruising in the scenic and remote Beagle channel went by with barely a single sign of any other human being, but barely a day went by without a trace of the beavers. From high on a windy mountain-top, overlooking the anchorage, one could also overlook the forests: dark green, but always streaked with auburn patches indicating the areas which had been felled and turned to swamp by a beaver family. Or one could see where milky liquid oozing from the foot of a crinkled white glacier had been carefully collected up into a bright, blue lake; and with the binoculars, pick out the inevitable brown dot of a beaver’s lodge in the centre of it.

From closer up, the effects of their behaviour were less scenic. In some places, every third tree bore the scars of a beaver’s teeth and the waterline was a row of old stumps. Even the smallest pond or stream harboured a lodge more often than not. While some beavers had occupied or enlarged existing areas of water, others seemed to have started from scratch. One lake we visited looked as if it had been flooded overnight: a forest of hundreds of dead trees were still standing somewhat eerily, their trunks submerged in the still water and their leafless branches looking as if they had been swept by a forest fire. It took us two or three hours, walking around the waterline and picking our way over huge trees lying strewn on the ground, to discover the single dam by which it had been created. The massive structure of logs, built with an inward curve to resist the force of the water, was considerably higher than a man and at least 15 or 20 metres long; and it had a top broad and strong enough to provide us with easy access to the other side of the river. One of the dam’s creators arrived as if to investigate the intruders, and it swam nearby in the water with it’s smooth brown head barely breaking the surface, before seizing a floating stick and diving out of sight with a loud splash of it’s tail.

A dam, and beyond it a lake created by this single blockage. Beavers must clearly be strategic in choosing where to build, and no less so in transporting lengths of trunk which are each many times the animal’s own weight.

Beavers are family animals – a young pair will bond for life; building and maintaining their lodge and the dams necessary to flood land and create their desired watery habitat. A lodge is ideally surrounded by water with it’s entrance beneath the surface to prevent non-aquatic guests: a hollow mound of sticks with comfortable living chambers inside, including a “hall” in which the wet arrivals dry off before entering their living quarters. Their daily – or sometimes nightly – routine consists of patrolling their territory to keep other settlers away, maintaining what can be an intricate system of dams, and building a stockpile of fresh wood underwater for future consumption. They meticulously repair their lodges before each winter, sometimes picking out and felling the required trees months in advance; and they are content to have their pond frozen over during the winter, swimming under the ice to access the aforementioned store – although if they run out of food one of them may face the unenviable task of making an opening in the lodge and venturing out into the snow to bring in new supplies. Every year the pair produces anywhere between one and four offspring, which are taught the trade of dam-building for a period of two years before they leave; and are expected join in with taking care of the next litter. They seem like sophisticated creatures, and they appeal to people for that reason.

Beavers where they belong are generally considered beneficial, or even essential – after all, they have existed peacefully in North America for millennia. American trees (such as willow and birches) which evolved alongside the tree-eating rodents are usually fast growing, and being felled seems to simply rejuvenate them. The beavers have a role in the hydrological cycle, trapping water with their dams, and there are apparently cases where this simple action has transformed a near-desert into an oasis; providing habitat for other species. And a wide array of animals, ranging from bears and wolves to eagles and alligators, take advantage of the beavers in a different way and prevent them from growing common enough to cause much damage to forests. The recent decline in North American beavers is considered bad news; and in Scotland, where beavers have been extinct for 400 years, it was actually decided to reintroduce them (but that decision, needless to say, was also highly controversial – to the extent that some of the animals released by those in favour of the project already seem to have been covertly butchered by the opposition…)

In South America, the situation is different. The trees (mainly of the genus nothofagus, or “false” beeches) can’t cope with beavers – a tree felled by a beaver in a single night is gone for good, and the large ones may be well over a hundred years old. With no predators and an endless supply of food and suitable habitat there are no limitations to the rodent’s numbers. Also, Patagonia is without the other species that take advantage of the beaver’s activities; the animals which depend on them to provide wetlands and the colonisers which ease the swamps back to their previous forested state. An area destroyed by beavers is destroyed for a very long time: decomposition in the flooded area raises soil acidity making it unsuitable for native plants, an effect which is of course not just local but extended to everywhere downstream of beaver dams. As the pond silts up, erosion sets in. The resulting sparse, inhospitable clearings are apparently serving as magnets for the invasive flora of Tierra del fuego – which includes typical European flowers such as clover, dandelions and daisies, creating a slightly nostalgic and very bizarre impression when viewed in front of Andean mountains and glaciers.

Scientists have only been able to compare the scale of this transformation of the forests to the one caused by the last ice age. Vast tracts of land have been laid to waste – even experiments in replanting the nothofagus by hand have been distinctly discouraging – and with plenty of room left to expand, it seems probable that the beaver’s invasion has barely started.

Once a large area of native woodland, this valley is now an expansive marsh criss-crossed with canals constructed by the beavers to facilitate the transport of wood. (Photo by Jill Schinas)

It didn’t take long for the Argentine government to become aware of its blunder and the need to get rid of the introduced beavers. Beaver trapping had never taken off – they even tried offering bounties for every pelt produced, but what little trade there was stopped as soon as the subsidies did. Either way, demand for beaver skin had diminished; and beaver meat, whilst it is edible, is apparently not particularly pleasant either. The authorities lost all patience, and launched a radical and brief campaign of blowing up beaver lodges with dynamite. The lodges were rebuilt within a matter of days by survivors or newcomers, resulting in more trees felled and even more damage than before. From then on the beavers have been left more or less alone.

When it comes to beaver eradication experts are divided, according to whether they consider the project just about feasible or ludicrously impossible. Certainly, it will be the most ambitious eradication of an invasive species which any country has ever attempted – if it ever is attempted. Ten years ago an estimate of the cost of removing the beavers came to $35 million. Small areas in which beavers have been successfully eradicated made use of every method and the latest technology they could lay their hands on: a coordinated army of helicopters and boats, teams of dogs and trappers. Total eradication would require picking over the enormous region as with a fine toothed comb, locating even the tiniest bodies of water in an area almost entirely uninhabited, barely explored, and inaccessible by anything except a boat, if that. Not to mention requiring perfect cooperation between the Chilean and Argentinian governments; which, to put it mildly, would be rather unusual.

There’s also another obstacle facing those who want to remove the beavers: a surprising number of people are adamantly against killing the invaders. It normally seems to relate to the animal’s building abilities. Although their penchant for architecture has been reliably proven to be due to instinct rather than intellect – and after all, cockroaches construct beautifully complex egg-cases, and I’ve never heard of anyone refusing to eradicate them on those grounds – beavers also happen to be cute and furry. Even better, they build “houses” and have a family life which can be roughly compared to that of humans, and they have a habit of crouching on their hind legs whilst manipulating branches with their “hands”. In the end, sympathy for the beavers is mostly just a demonstration our anthropomorphic tendency to compare them to humans, and to assign them with a personality similar to Bob-the-Builder’s. Beavers are unlikely to be much more intelligent than other rodents such as rats – which they rather resemble; and which, incidentally, people rarely have any moral issues with killing off in the inhumane ways imaginable.

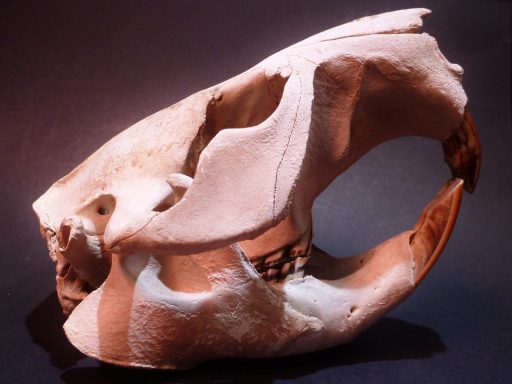

Made for destruction – a beaver skull, which I found in an area of swamp, displays the impressive incisors necessary for felling massive trees.

I have come across a few serious remarks from more than one person who acknowledge that the beavers must be removed from the forests, but insist that since “it isn’t the beaver’s fault” the only morally right solution is that they should be gathered up in pens in order to live out their natural lives. (Surely it would be more realistic just to fly them back to Canada – especially since they now seem to have a shortage up there…) Or see this petition – I’m not sure who to – stating that “the humane solution would be to let mother nature control the invasion.” (Humane to the beavers, perhaps, but what about all the other wildlife in Chile and Argentina?)

On the opposite end of the scale is a friend who produced some photos taken during an evening stroll on the beach outside his house; and several were of a gorgeous young mink, it’s soft brown fur set off by the orange sunset as it played amongst the rocks at the water’s edge. “Unfortunately, I was unable to kill it,” he explained delicately. “I was accompanied by a friend, and I felt that it would have been in bad taste.”

It seemed harsh – but not quite so harsh when I remembered that the site of his walk was also a sea bird colony, and the mink’s play had probably been less than innocent. The minks were introduced under similar circumstances to the beavers, and they are currently decimating native bird populations. In some anchorages we visited they practically swarmed at dusk amongst the rocks on the water’s edge – the speed at which they slip in and then out of the water, taking only a few seconds to bring ashore a fish or a crab, is both entertaining and alarming. The removal of that mink, whilst it certainly would have been “in bad taste”, would undoubtedly have made all the difference to some of the young chicks which hatched during that season. Protests against eliminating these invasive species would seem to be less grounded in reasonable compassion, and more based on the fact that the idea is distasteful – and it might be better from the ecological point of view if the realistic and unsentimental attitude were more common.

Last spring, while we were at the local yacht club, a small beaver came swimming down the creek, splashing around the moored boats before eventually clambering out onto the beach. It spent half an hour sitting in the sun slowly sorting through the pebbles like a toddler at the sea-side, exploring them with its little black hands and raising each one to its mouth before letting it fall. It seemed so absorbed in study that it took no notice when I approached, and was equally unconcerned when I put a hand on its back. The outer hair was wet and coarse, while a second water-proof inner layer was as soft and downy as a newly hatched chick – insulation, no doubt, for swimming in glacial waters. Its dark little eyes showed no suggestion of intelligence, but teeth gave away its profession – long, curved, yellow chisels sharp enough to create piles of neat wood chips around the stumps of felled trees. I imagine it was a youngster, who had probably recently parted from his or her parents and was travelling in search of a new territory, to set to work gnawing down enough trees to build dams, and a lodge in which more beavers are probably already being raised.

I’d be the first to admit beavers are charismatic – but they certainly don’t belong here in Tierra del fuego.

Melt-water from the glacier has been commandeered on it’s way to the sea. The arrival of these beavers seems quite recent, and this green patch of forest will probably soon be turning brown.

One thought on “Beavering Away”